No one likes having the difficult conversation whether it is in his or her personal life or at work. Unfortunately they often are essential.

No one likes having the difficult conversation whether it is in his or her personal life or at work. Unfortunately they often are essential.

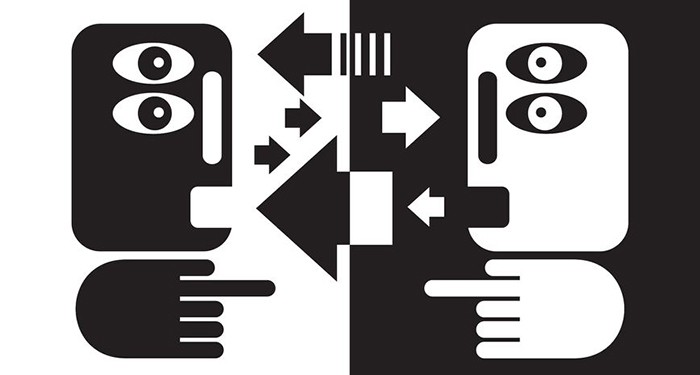

What makes the interaction scary is the unpredictability of the response and reaction of the receiver as well as your issues about the topic at hand.

I prefer to use what I call the “long form” approach to trying situations. Long form, just like with your tax return, has more details, backup information, and demands more time than a simple chat. The intention is getting better, long lasting results and, in some cases, because it is required.

The three essential steps to having a difficult conversation are Preparation, Listening, and Engagement.

Preparation: This is probably the most important and the most overlooked aspect of having the difficult conversation. Before sitting down, writing the e-mail (not the best tool for the job), or making the call (also not ideal), you have to know the entire story. A good dose of skepticism is called for. Do you have the complete picture, with a substantial piece of the history, and have you talked with all the players involved? Is there data to back up what is being delivered as truth? And, have emotions superseded logic?

This kind of investigation takes time and skill. You also need to leave any preconceived notions and prejudices aside as your goal is to deliver a clear and accurate picture to the person you are going to be speaking with. At times, a trusted colleague or support professional in human resources can help you but the onus is squarely on you.

Once you are confident you have the entire picture, you’re then ready to prepare how and where you are going to convey the message. I was always a fan of practicing out loud either to myself, or better yet, to someone I trusted and valued. You have to hear the language, not just think it. You also want your delivery to be smooth and neutral. Granted, you get better with experience but overconfidence can be a recipe for disaster and increased liability.

Listening: We often get so invested in what we are going to say we fail to hear to the response. And it’s the feedback that should drive the conversation. We’ve all heard about and practiced active listening with repeating back to the speaker in a way he or she will feel you understood. You also know that body language is as important as what you say. Yes, we know all of that but do we actually practice it, or when we are under the gun, do we do what we know or feel comfortable with?

Predicting emotional reaction can be the most daunting. Will the person get angry, sad, blame, or stonewall? You can never be certain but you can probably have a good sense if you know the person and have observed his or her behavior in the past. Granted, all of us have our flashpoints and we are all capable of being surprised.

I’ve been taken aback in a difficult conversation when the other person brought up a perspective or fact that is valid or one I had not thought about. The temptation is to skip over it and say, “I hear you but…” and go back to your prepared remarks. There’s the potential for losing important insight and rethink. Also, maybe your decision was wrong or incomplete.

Finally, Engagement: The goal of a difficult conversation is for some sort of shift to occur. That’s hard if you have not engaged the other party. Engagement is a skill. Some of us are better at it than others but everyone can learn (big plus in social situations). It’s a behavior that encourages the search for common ground and strives to achieve a comfort level, so both parties can interact, agree or disagree, and accept the end result (even though one or both might not like the outcome).

Curiosity is the best trait to possess if you really want to engage. Go into that difficult conversation really wanting to hear what the other person has to say, observe his or her reaction. Try to see things from their perspective even if you don’t agree or the decision has been made and you are strictly informing them. Engagement also helps the listener take in the information. They hear your points rather than spending the time conjuring up their next defense. Engagement also allows people to move on, either in future interaction or with their lives. “I didn’t like what she had to say but must admit she had her facts straight, let me talk, and gave me the sense it wasn’t a one way conversation,” would be a measure of success.

I’ve had difficult conversations with people who in the end thanked me; I‘ve also had some where they walked out in the middle; a majority fell somewhere in between the two. Looking back, I must admit that had I followed my three steps fully, the second scenario might have been prevented.

Anyone who tells you having the difficult conversation is “easy” or “not an issue” is either lying or cruel. Even those of us who have been involved in them for many years don’t relish the encounter or feel confident that we can predict the outcome. What we can say is that because we have prepared, are open to listening, and willing to engage, we have set the stage and entered with the right mindset to position the meeting for success.

Leave a Reply